In my previous two YouTube writeups, we were limited by having to know the victim’s private video IDs to do anything with them. Let’s be honest, that’s a bit hard to exploit in the real world. Thankfully, I found another bug that solves this problem once and for all. Allow me to present a real, one-click steal-all bug to you. This one actually kicks-ass. At least I like to think that.

Prefer to read the raw technical report I’ve sent to Google instead of the story? You can find it here!

It all started years ago. We were at a friend’s place and were flying tiny little FPV drones. After draining all of the miniature drone batteries, I wanted to show them an old personal video from my YouTube account. They had a Smart TV. I opened the YouTube app on my phone, selected my private video, and it gave me the option to play it on the TV. I thought why not, let’s do that, so we watched my private video on the TV without problems. But this planted an idea in my head that stayed there for years. My question was very simple:

How the hell did the TV play my private video?

I was not signed into the TV. And only I can watch my private videos right? Did it somehow log the TV into my account temporarily? But then could the TV access all of my other private videos as well? I hope not?

A few years later, in 2020, I crossed paths again with a fellow LG smart TV. I remembered my question about the private videos, and now as I was actively working on Google VRP and YouTube, I decided to investigate.

OK, so a good starting point would be to look inside the YouTube for Android TV App. That’s probably a huge and complex Android application that would take forever to reverse-engineer right? Wrong. Turns out, it’s just a website. Looking back, I was such a boomer to expect anything else. Nowadays even your toothbrush is running a WebView.

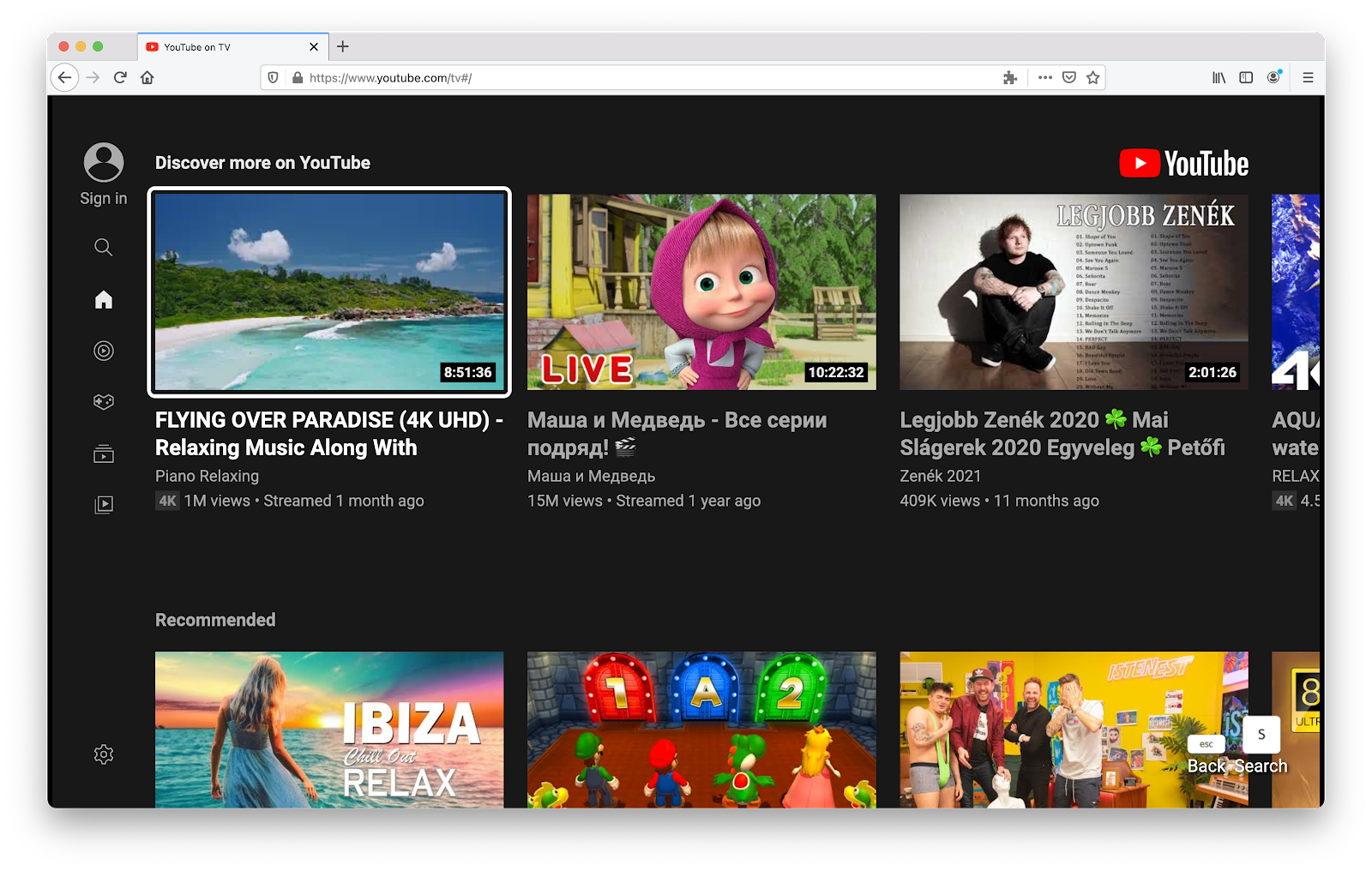

After looking into the decompiled APK, I found that it simply loads https://www.youtube.com/tv into some kind of weird WebView like browser, which is called Cobalt. Fair enough, that’s good news. We can just open https://www.youtube.com/tv in the browser, and start testing. So I opened the page:

But wait! I don’t want to be redirected! Show me YouTube TV!

There must be a way by which YouTube decides if I am a TV or not. After finding no other option, I thought it must check the User-Agent header, so I tried modifying it:

// change ‘Firefox’ to ‘Cobalt’ in the User-Agent

“User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:87.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/87.0”

->

“User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:87.0) Gecko/20100101 Cobalt/87.0”

Changing Firefox to Cobalt in the initial request worked, and the request returned the full YouTube TV app, instead of the “You are being directed to youtube.com” screen:

Boom! Awesome, we are a TV now and can start testing!

This is where writing this blog post gets a bit difficult. The feature I used to test this has been fully removed from the desktop YouTube site after my bug report. (coincidence? 👀) At the time I didn’t really document my research with screenshots (lesson learned), so unfortunately I will have to rely on public pictures / my memory to tell you about this feature.

So I wanted to see how this “remote-control” works. At the time, you were able to control a TV via the desktop YouTube site as well (https://www.youtube.com/), even if you were on a different network than the TV. I used this for testing, but this is the feature that got removed. (From the UI.)

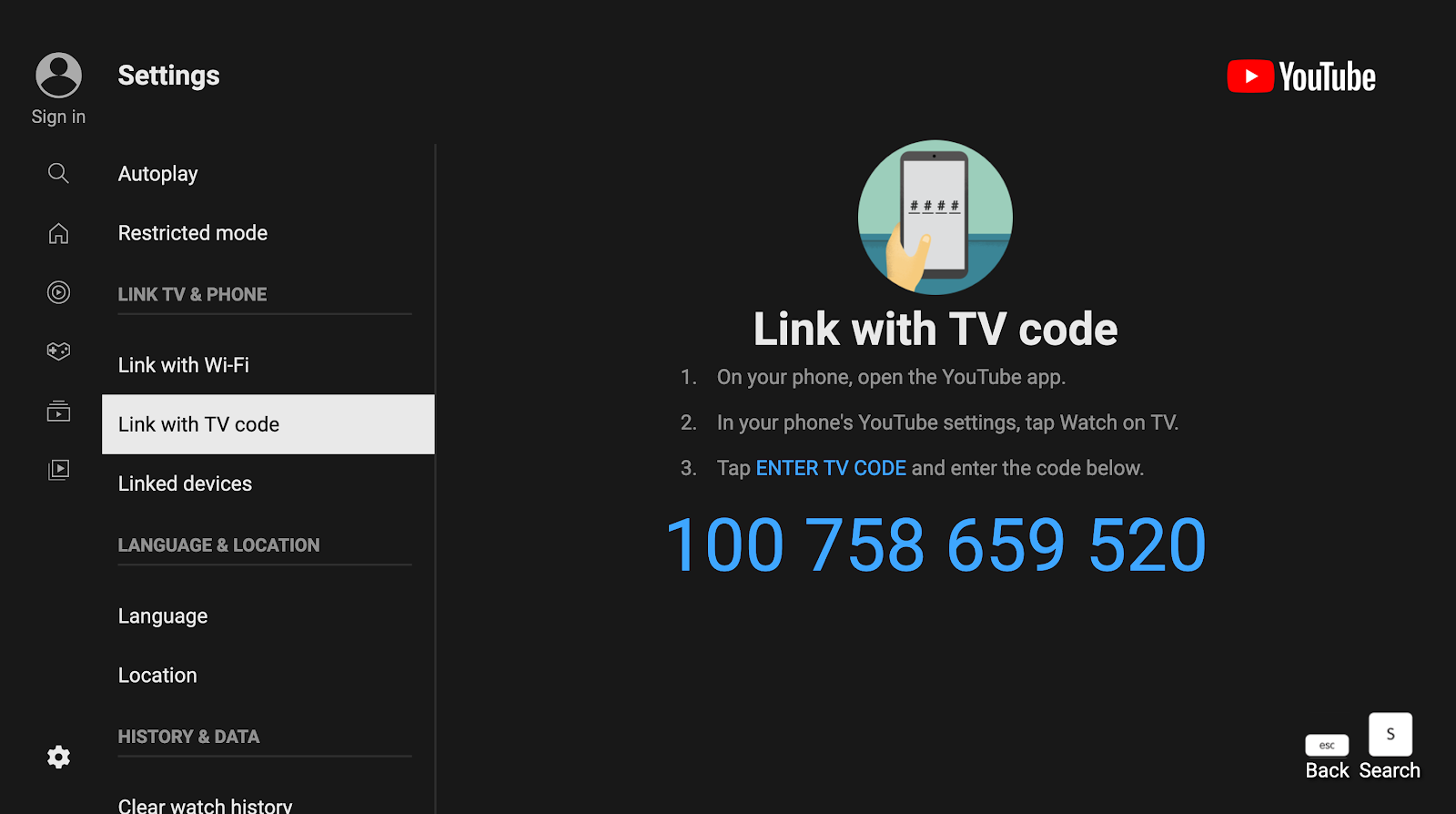

To link a TV, you would have to enter its TV code. So on my “TV”, I generated a TV code…

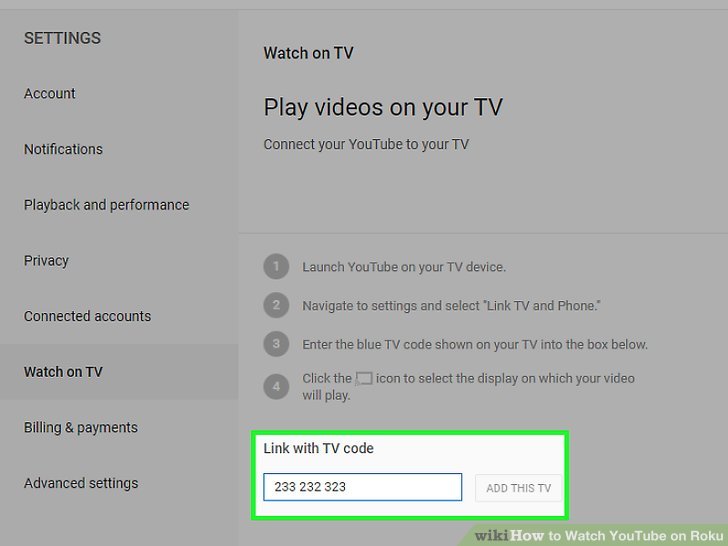

And entered that TV code in my other browser, on https://youtube.com/pair:

src: wikiHow

src: wikiHow

After linking a TV, if you opened a video, a little Play on TV icon appeared on the right side of the player, which if pressed, transferred the video onto the TV:

src: www.technipages.com

src: www.technipages.com

And guess what, it even worked with private videos! I finally had all the tools to get to the bottom of this.

The internal API that provided this remote control capability was called Lounge API. The pairing process looked like this:

- The TV requests a

screen_idfrom/pairing/generate_screen_id - Using the

screen_id, the TV again requests alounge_tokenfrom/pairing/get_lounge_token_batch - With the

lounge_token, the TV requests a pairing PIN from/pairing/get_pairing_code - The TV displays the pairing PIN

After this, the user has to enter the pairing PIN on their device. With the PIN, the user’s device calls /pairing/get_screen, and if the user entered a correct PIN, the Lounge API returns a lounge_token for the user as well. After this, the pairing is over. The user can now control the TV using the lounge_token it just obtained.

Interested in how the pairing process looks like on a local network where you don’t have to enter a TV code? I tested it with a Samsung TV and here is what I found.

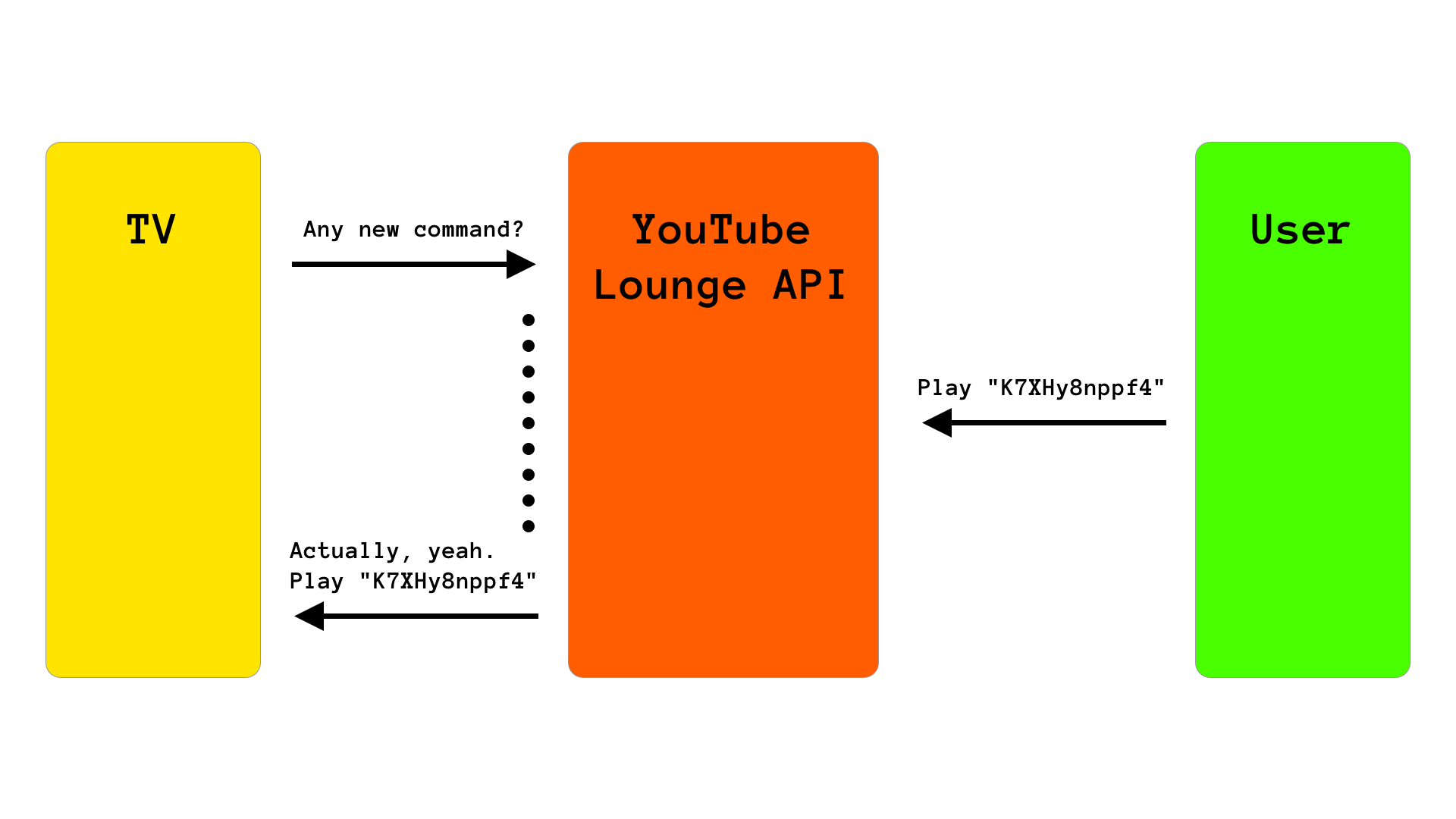

After starting the pairing process, the TV switches into a “polling” mode, which is quite a common thing at Google. Instead of WebSockets, Google usually uses these bind requests, which are basically HTTP requests that take very long if there are no new events, but return immediately if there are some. And the TV calls this /bind endpoint over and over.

This HTTP polling might seem weird for you, even if you are a web developer. Here is an example:

As you can see, the TV sends a request to the /bind endpoint, asking if there are any new events. Since there are no events at the moment, the Loung API doesn’t yet respond and keeps the HTTP request waiting. For the TV it looks like the request is still loading. But, as soon as the user sends a new command request to the Lounge API, the API returns the HTTP request to the TV with the new event. After this, the TV sends the /bind request again and waits for new commands. This gives the “real-time remote control” feeling, but without WebSockets. (Of course, if there are no events at all, the /bind requests still return with an empty body after a while, to prevent the requests from timing out.)

“But you still didn’t tell me how it plays the private videos!! I didn’t come here to read about WebSocket alternatives.” - You might be thinking. And you are right. Here it goes. Get ready for the epic answer to the mystery that kept me up at night for years:

It uses an extra video-specific token, called ctt.

Eh. Hope I didn’t hype that up too much.

So, when the user requests to play a private video, the event the TV receives from the /bind endpoint includes an extra ctt parameter next to the videoId. When playing the video, the TV then requests the raw video URL from the /get_video_info endpoint and includes the ctt token as a GET parameter named vtt (for some reason). Without the ctt token, the TV can’t watch the private video.

This ctt token only gives permission to watch that specific video, so my fear I mentioned at the start of the blog post (that the TV can access my other private videos) is not true. But if you find a bug that makes it possible, make sure to write a blog post about it!

So, what’s the bug?

Now that you understand how this real-time remote control magic works, let’s see what the actual bug was.

While playing with this API, I was looking at the logs in Burp, my HTTP proxy of choice. More specifically I was looking for the one specific request that the browser made, which actually started playing the video on the TV. There were a bunch of requests, so it felt a little bit like finding the needle in the haystack, but eventually, I found the one that triggered the event. I was able to repeat it with Burp, and start the video manually over and over on the TV, just by sending one request.

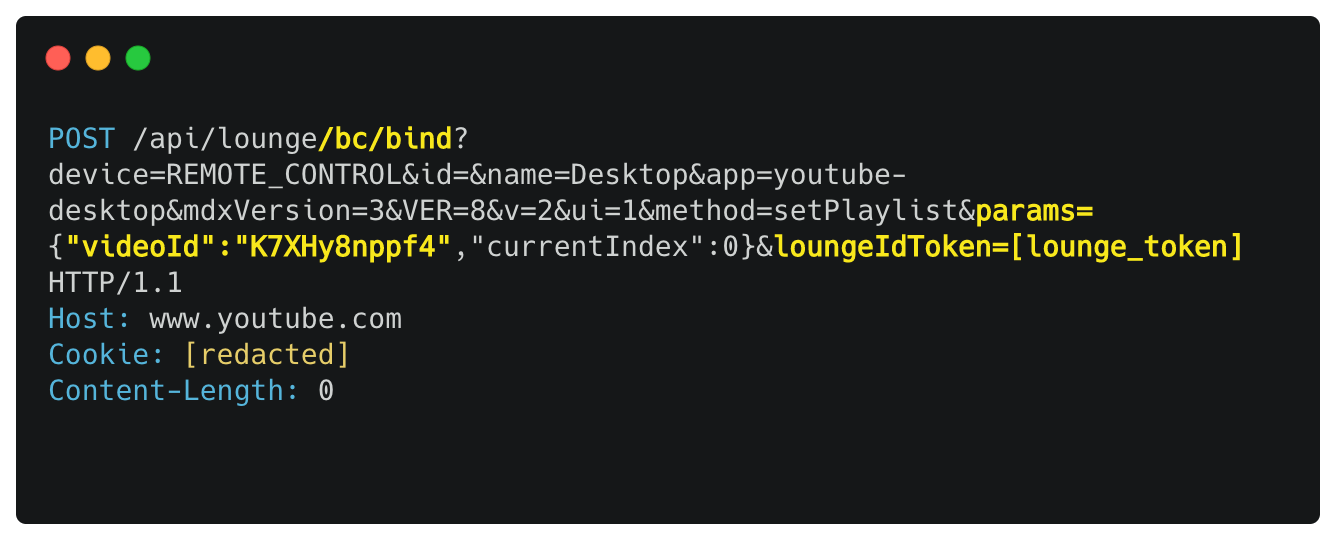

It was a POST request to the /bind endpoint. It had a crazy amount of parameters. 90% of which was not required for it to play the video on the TV.

While trying to make sense of this request and its insane amount of parameters, I noticed that something was missing… I didn’t seem to find any CSRF tokens anywhere. Not in the GET parameters, not in the headers, nowhere.

(Are you unsure about how a Cross-Site Request Forgery attack looks like? Watch this video by PwnFunction before continuing!)

I thought “hmm, that’s weird. It has to have some CSRF protection. I’m probably just missing something”. I tried removing more and more unnecessary parameters, and it still played the video on the TV. At one point, the only long and unpredictable parameter in the request was the lounge_token and it still played the video on the TV. Still, I thought I have to be I’m missing something. So I made an HTML page with a simple form that made a POST to the Lounge API to simulate a CSRF attack.

I opened my little demo CSRF POC page and clicked the “submit” button to send the form, and the video started playing on the TV! BOOM! At this point I finally accepted that this endpoint really doesn’t have any CSRF protection!

So the /bind endpoint doesn’t have CSRF protection. What does this mean?

It means that we can play videos in the name of the victim if she visits our website! We just need to specify the lounge_token in the POST request, and the ID of the video to play, and send the request in the name of the victim, from our malicious site.

Since we are making the play request in the name of the victim, if we specify a victim’s private video to play, the TV targeted by the lounge_token will receive a ctt token for it, which will give the TV access to the private video…

This is what the video playing request without any CSRF protection (and without all of its unnecessary parameters) looked like:

Don’t worry if you don’t know what some of these parameters mean. I don’t know it either. And it had like 10x more originally.

“But wait! How do we know what TVs the victim used before? How do we get a lounge_token? This can’t be exploited, right?” - You might ask.

Actually, it can be exploited. What if I told you, that we can build our own TV?

Image this attack scenario: We “make our own TV”, get a lounge_token for it, and then make a request in the name of the victim to play the victim’s private video on our “TV”. After this, we poll the /bind endpoint with our “TV”, waiting for new play events, and when we get it, we will also get the ctt for the victim’s private video, so we can watch it! That’s not bad!

To exploit this, we don’t have to use the actual YouTube TV site, it’s enough to extract the essentials from it, and build a little script that behaves like a “barebones TV”. So that it can generate a lounge_token for itself, and poll the /bind endpoint for new play events.

If you are waiting for the “pin pairing” steps, we can actually skip those completely by just using the lounge_token returned to the TV from the initial /pairing/get_lounge_token_batch request.

But we are hitting the same exact wall that we hit in both of my previous writeups! How do we know the victim’s private video IDs? In the beginning, I told you that this bug will have a solution for this problem. And indeed it has!

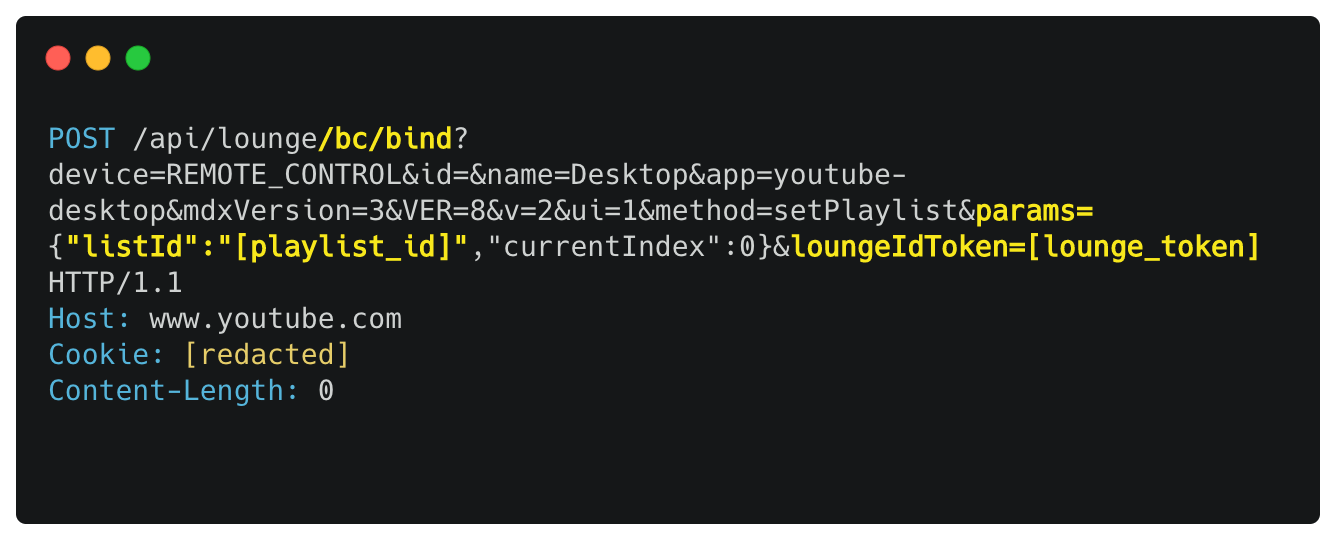

The magic here is that we can not only play videos, but we can even play playlists on the TV using this vulnerable request!

By changing the videoId to listID in the POST request, we can specify a playlist to play on the TV, rather than a video:

When specifying a playlist like this in the POST request, the TV will get a play event from the Lounge API with a list of video ID-s that the given playlist contains.

But what playlist should we play in the name of the victim?

In my previous YouTube writeup, I talked about the special Uploads playlist. It’s special because if the channel owner views that playlist, he/she can see all of her Public, Unlisted and Private videos in it. But if a different user views the same playlist, she can only see the Public videos in it.

The ID of this special Uploads playlist for a given channel ID can be found easily:

// just have to change the second char of the channel ID

// from ‘C’ -> `U` to get the ID of the special “Uploads” playlist

“UCBvX9uEO0a3fZNCK12MAgug” -> ”UUBvX9uEO0a3fZNCK12MAgug”

The channel ID is public for every YouTube channel, most of the time it can be found by simply navigating to the channel’s page on YouTube, and checking the URL:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/[channel_id]

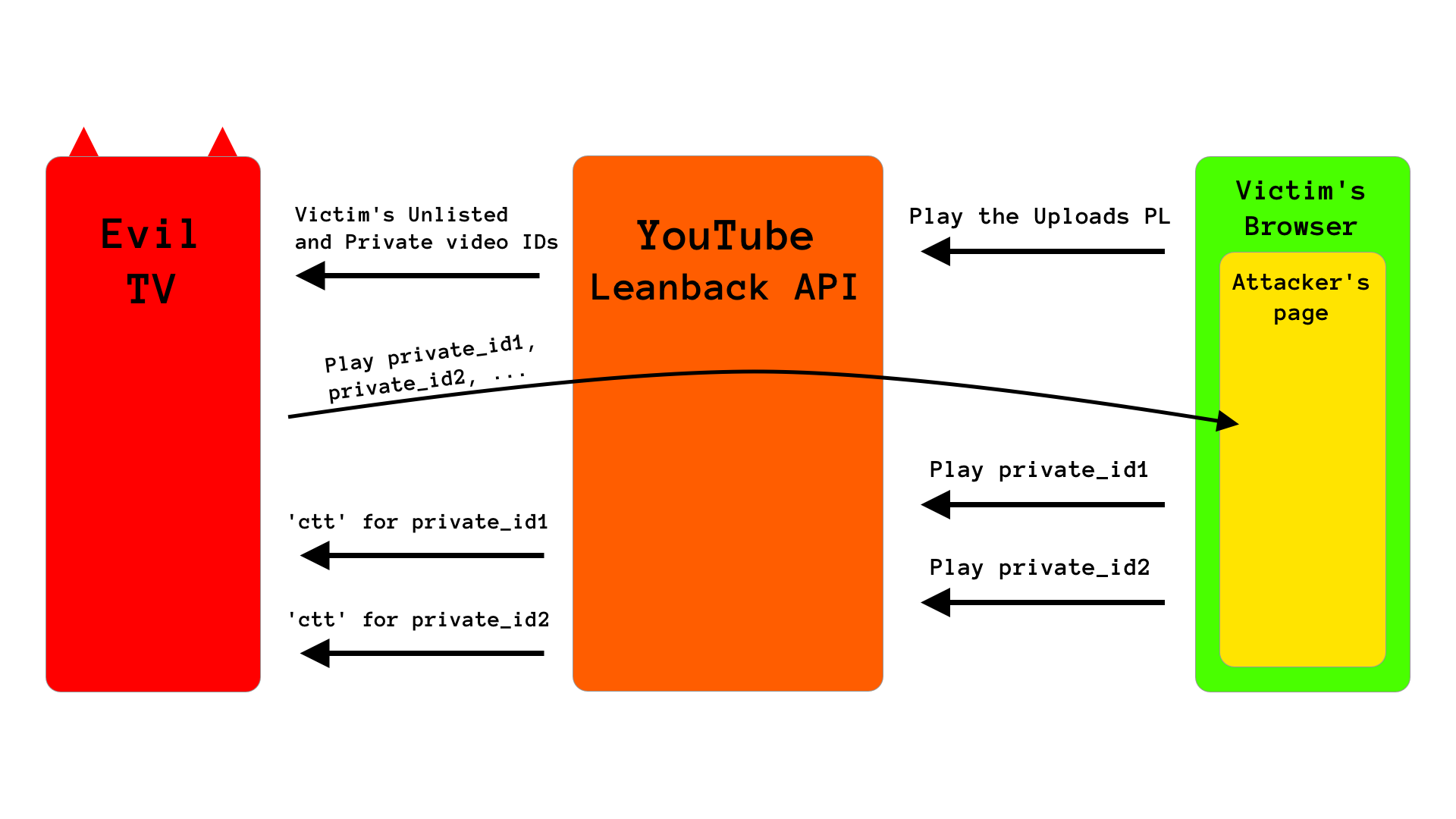

So, if using our CSRF vulnerable POST request, we play the victim’s special Uploads playlist in the name of the victim on our malicious TV, our malicious TV will get all of the victim’s Public, Unlisted and Private video IDs!

And we already know how we can steal the ctt for a private video if we know its ID.

So, to sum it all up, we could make an absolutely ridiculously epic POC which steals literally everything from the victim, by performing these simple steps:

- Set up a malicious page specifically for the victim by hardcoding her channel ID, and make the victim open it in her browser

- With our malicious page, make the victim play her

Uploadsplaylist on our evil TV - With our evil TV, listen for the play event and note the victim’s video IDs (including

Unlisted&Privatevideo IDs) - With our evil TV, tell our malicious page to play all of the

Privatevideo IDs one by one on our TV, so we can steal all of thectts from the play events our TV gets - Profit!!!

Here is diagram of this high-level attack flow:

That’s it! We have stolen all Unlisted and all Private videos of the victim! Now we’re talking!

(actually, we could also steal the contents of private playlists, liked videos, and the watch later playlist with the same trick. but that’s not that exciting.)

This bug was a bit complicated to exploit, so I made an extremely overengineered POC script, which performs this attack automatically. This is how it looked like in action, stealing all Private & Unlisted videos of a victim:

The POC had two components, a backend webserver which also acted as the evil TV, and a frontend which was running in the victim’s browser, talking with the backend. It’s perfectly fine if you don’t exactly understand how the script worked under the hood, I might have made a little bit of a mess (but you are welcome to look at all of the source code if you are interested!). Here is a more (or less) fun, higher-level description of the POC flow (that I have sent to Google):

- POC starts a Flask webserver to serve the victim opening the malicious page. Let’s call the POC Python script

backend. - The victim opens the malicious webpage. Let’s call the victim’s page

frontend. - The

backendrequests the attacker to enter the victim’s channel ID. - The channel ID’s second character is changed to a

U. The resulting string is the ID of the victim’sUploadsplaylist, which contains allPrivateandUnlisteduploads. Only the owner can see thePrivateandUnlistedvideos in this playlist. Other users only see thePublicvideo IDs. - The POC sets up a fake TV and starts to poll the events for it.

- The

frontendis instructed to execute the CSRF request and play the playlist generated inStep 4.on the malicious TV. - When the CSRF request is sent by the

frontend, thebackendreceives the TV play event, containing the IDs of all of the victim’s videos, includingPrivateandUnlistedvideo IDs. - The

backendqueries the YouTube Data API with all of the obtained video IDs to find out which videos arePrivateorUnlisted. - The

Unlistedvideos are ready, thebackendprints its IDs out for the attacker. TheUnlistedvideos only require knowing the video ID to watch. - The

backendinstructs thefrontendto play the victim’sPrivatevideos on the malicious TV one by one. For every video, thebackendsets up a new malicious TV, tells thefrontendto play the specific video, listens for play events, and receives the event for the TV with a specialcttparameter. Using thectt, thebackendqueries theget_video_infoYouTube endpoint for the specificPrivatevideo, authenticates itself with thectt, and greps thePrivatevideo’s title and direct video URL from the response. - After every

Privatevideo is played by thefrontend, thebackendprints the details of all of the obtainedPrivatevideos for the attacker. - The POC script is done.

Once again, you can find the source code of the POC files here.

The fix:

YouTube fixed this issue in a quite simple, but effective way. They removed the whole feature. :D

No, actually, what they did is that this /bind endpoint now requires an Authorization header with an OAuth Bearer token to be authenticated, so the mobile apps and such can still use it without issues. But when requested with cookies only (like in our CSRF attack), it behaves like an anonymous request, without any authentication. Thus, it’s not possible to play videos/playlists in the name of a victim anymore.

Hey, you read the whole thing!

I made an experimental Google Form to get a little feedback about you & your experience reading this writeup. If you’d like, you can fill it out here.

Timeline:

[Jul 24, 2020] - Bug reported

[Jul 24, 2020] - Initial triage (P3/S4)

[Jul 29, 2020] - Bug accepted (P1/S1)

[Aug 04, 2020] - Reward of $6000 issued

[??? ??, 2020] - Bug fixed